Some years ago I gave a lecture to a local literary society, which I then repeated for the WEA. The subject was Louisa Alcott’s work outside of Little Women and we explored her love of writing gothic stories, as well as her experiences as a nurse during the American Civil War. Below is the first half of the lecture which introduces her gothic writing, which she referred to as her ‘blood and thunder tales.’

Let’s start with a well known beginning:

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents” grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.

“Its so dreadful to be poor!” sighed Meg, looking down at her old dress.

“I don’t think it’s fair for some girls to have plenty of pretty things, and other girls nothing at all,” added little Amy, with an injured sniff. “We’ve got Father and Mother, and each other” said Beth contentedly from her corner.

You may well recognizable this as the beginning to Little Women, a novel which has not been out of print since its initial publication in 1868. As well as being a memorable beginning, it is effective in establishing the character types of the four main players:

- Jo as the focaliser, her personality already coming through as lying on the rug would not have been ladylike behavior in the 19th Century.

- Meg, the eldest sister, often concerned with her appearance (and frequently frustrated by Jo’s)

- Petulant Amy, the youngest of the four.

- And the somewhat saintly and home-loving Beth.

The Little Women series of novels is the work Louisa Alcott is most remembered for, yet Little Women is the novel she least wanted to write, declaring she didn’t know how to write for girls. When Little Women was published in 1868, she was more well known for writing lurid gothic thrillers and as the author of Hospital Sketches, a fictionalized account of her experiences as a nurse in the American Civil War.

Like the eponymous Jo March, Louisa was the second of four sisters, lived most of her life in poverty, and often worked to support her family. The form of her employment varied from writing, to teaching, to sewing, to working as a companion to wealthier friends and relatives, from which she secured an expenses paid trip to Europe. The family’s lack of financial stability resulted from the unconventional lifestyle of her parents Amos Bronson and Abba May Alcott.

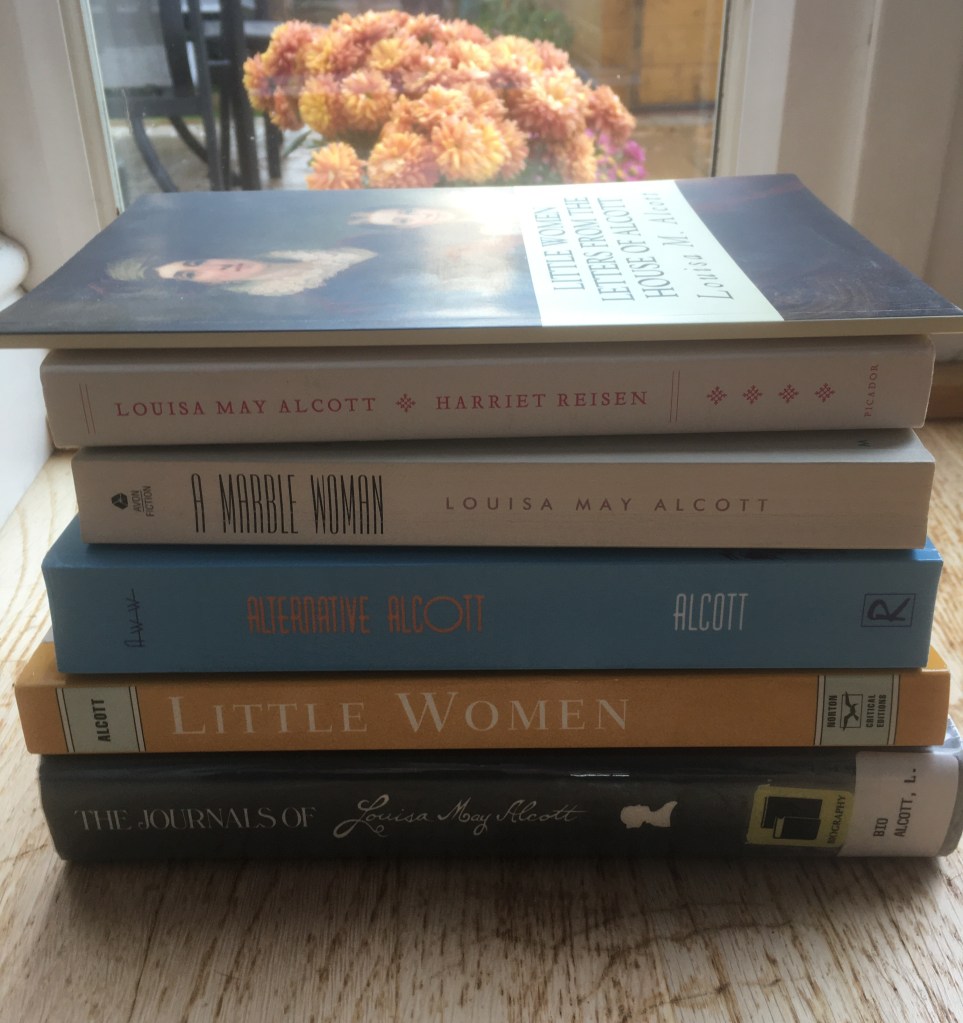

Her writing output was prolific – at least 270 works ranging from poetry to novels to essays. These included 9 novels and 16 short story collections which would now be placed in the genre of young adult fiction; 4 adult novels – Moods (1864), Work (1873), A Modern Mephistopheles (1877), and Diana and Persis (1879). In addition, she wrote lots of melodramatic gothic works under the gender neutral name A.M. Barnard.

She called her thrillers her ‘Blood and Thunder tales’. Themes such as secret family curses, murder, revenge, domineering men, manipulative women, drugs and incest featured in these tales. These appeared in popular magazines, some were short stories, others were novellas, and most of them were written under her pseudonym A.M. Barnard.

For many years these works were lost until they were discovered in the Harvard library by scholar Madeleine Stern and rare book collector Leona Rostenberg. In 1943 on a research visit to the library they realised Louisa Alcott and A.M. Barnard were one and the same. Their excitement was immense at having discovered these works. They were not allowed to remove them from the library, instead they had to painstakingly copy all of these works by hand. Although the discovery was made in 1943, it was not until the 1970s that some of these lost works were re-published.

One of her longer thrillers – A Modern Mephistopheles, was published anonymously in 1877, after the success of Little Women. This featured the character Jasper Helwyze who gives hashish to the heroine. However, most of her thrillers were written before her fame as a way of providing financial support to the family. These bore titles such as ‘Norna; or The Witch’s Curse’, ‘The Captive of Castile’, ‘The Moorish Maiden’s Vow’, ‘Pauline’s Passion and Punishment’, ‘The Mysterious Key and What It Opened’ and ‘The Abbott’s Ghost or Maurice Treherne’s Temptation.’

Rather like Jo March in her garret, Louisa wrote stories such as ‘The Rival Prima Donnas’ where a singer takes vengeance by crushing her competitor to death with an iron ring. Since Louisa’s stories were rediscovered, a number have been collected and republished. ‘A Marble Woman’ is an eerie tale of domineering males, submissive women, opium addiction and possible incest. Drugs also feature in her work ‘Perilous Play’ where a group of young adults at a picnic experiment with hashish laced candies, almost ending in disaster.

‘The Abbot’s Ghost: or Maurice Treherne’s Temptation’ is set in a haunted English abbey and has quite a Dickensian feel to it. The cast of characters sit around a hall fire telling ghost stories about haunted houses, coffins and skeletons. Edith Snowden is Louisa’s strong willed woman with a mysterious past in this tale. ‘A Whisper in the Dark’ was a mystery story about Italian refugees, a spy, and a woman disguised as a man.

‘Pauline’s Passion and Punishment’ is another tale of vengeance with the manipulative protagonist Pauline enacting punishment on her fiancé Gilbert Redmond who breaks off their engagement in order to marry a much wealthier woman. Like many of Alcott’s female characters, Pauline is socially disadvantaged. Although born to a wealthy family, she is reduced to working as a governess. The plot is highly melodramatic as Pauline enacts a plan to marry a younger man as well as making her former fiancé fall in love with again, simply so she can reject him. The young sensitive Manuel has fallen in love with her and offers to kill Gilbert, however, she refuses, proclaiming:

“There are fates more terrible than death, weapons more keen than poniards, more noiseless than pistols… Women use such, and work out a subtler vengeance than men can conceive. Leave Gilbert to remorse and me.”

She does, however, persuade Manuel to marry her as she needs money in order to finance her revenge. She does not deceive Manuel regarding her motivations though and explains:

“I want fortune, rank, splendor, and power; you can give me all these… I desire to show Gilbert the creature he deserted no longer poor, unknown, unloved, but lifted higher than himself, cherished, honored, applauded, her life one royal pleasure, herself a happy queen”

The story is full of suspense which builds during the search for Gilbert and his new bride but I don’t wish to spoil the ending. The story won a $100 dollar prize in a writing contest which helped with Louisa’s expenses in taking up her post as a Civil War nurse in Washington DC.

Although Louisa did not publicly acknowledge her blood and thunder stories, and distanced herself through the use of her pen name, letters and journal entries indicate she enjoyed writing them:

“I think my natural ambition is for the lurid style. I indulge in gorgeous fancies and wish that I dared inscribe them upon my pages and set them before the public.”

The main publishers of Louisa’s Blood and Thunder tales were The Flag of our Union as well as Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. In Little Women these become the Blarneystone Banner and Weekly Volcano. One of her letters stated:

“I intend to illuminate The Ledger with a blood & thunder tales as they are easy to ‘compoze’ & are better paid than moral works.”

Indeed, each story earned her between $50-75, which is roughly the equivalent of $2000 – $3000 today. Although the characteristics of these works clearly placed them within the gothic genre, her works are differentiated by her concern with character development. Gone were the trembling, submissive heroines usually associated with 18th and 19th Century Gothic. Her works are well worth a read if you like gothic fiction with a more active heroine. Alcott’s women were strong, even if many of them were evil.