This is the second half of the lecture began in an earlier post. In this post I focus on Louisa Alcott’s time working as a nurse during the Civil War and some of her later writings inspired by her experiences.

In some ways, the Civil War functioned as a liberating experience for Louisa. By this point in her life, she had endured some difficult years. She had lived through the death of one sister and the marriage of another. Her hopes for education and independence were unrealised, partly due to the conventions of 19th Century life for women and partly due to years of family poverty.

Her family were politically active as strong supporters of the Abolitionist movement and at one point, they harboured a fugitive slave. Although she often thought of herself as ‘the family’s son’ she remained frustrated that her gender limited her ability to be involved in political activism. On the outbreak of war, her journal entry read:

I’ve often longed to see a war, now I have my wish. (12 April 1861)

By November 1862, she was almost thirty years old, and her diary revealed the formation of her plans:

Decided to go to Washington as a nurse if I could find a place. I love nursing and must let out my pent up energy in some way. I set forth… feeling as if I was the sone of the house going to war.

Nursing offered a respectable way for women to become involved in the war effort. A lady by the name of Dorothea Dix, the superintendent of Union Army Nurses issued a call for volunteers stating they should be married and “past 30 years of age, healthy, plain almost to repulsion in dress and devoid of personal attractions.” The rule regarding marriage was relaxed following an influx of casualties from the Battle of Bull Run in the summer of 1862.

On 11 December 1862 Louisa received her orders to leave the following day for Washington Union Hospital, Georgetown. The journey was an arduous one of 500 miles and included a train to New London, Connecticut, a steamship from Boston to New Jersey, and finally a train to Washington DC. She wrote of passing the brightly lit White House and the unfinished dome of the Capitol Building.

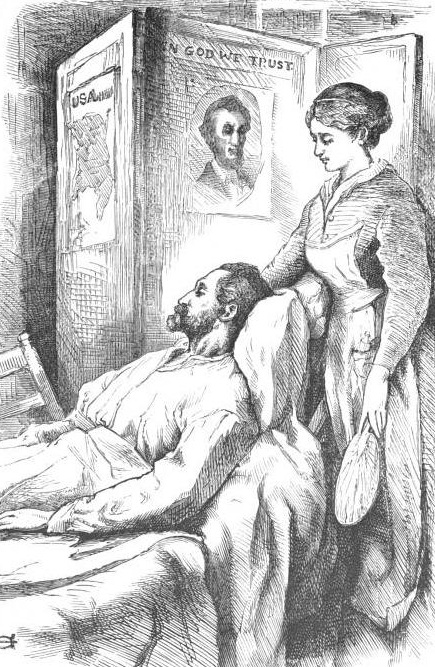

The Union Hospital was a hastily converted hotel. Her journals reveal it was badly lit, crowded and poorly ventilated as some of the windows were nailed shut. Others has smashed panes covered by curtains to keep out drafts. On arrival, she was put in charge of forty soldiers who were suffering from rheumatic fever. After only three days, there was a influx of wounded soldiers from Fredricksburg. She was give block of brown soap and a washbasin and told to wash them as fast as she could, which she proceeded to do for the next twelve hours. By the next day, she was required to assist with amputations. As you can see, there was no training to ease nurses into their duties.

One of her responsibilities was to assign patients to the appropriate areas in the three room ward. This was organised as:

- Duty room – recently wounded soldiers

- Pleasure room – recovering soldiers

- Pathetic room – soldiers with little or no chance of recovery.

Christmas and New Year came and went, and her diary entry for 1 January 1863 reveals she was rising to the challenge:

Five hundred miles from home, alone among strangers, doing painful duties all day long, and leading a life of constant excitement in this great house surrounded by 3 or 4 hundred men in all stages of suffering, disease and death. Though often homesick, heartsick and worn out, I like it.

However, her career as a nurse was not destined to be a long one. After weeks of nonstop work, poor food, stale air and exposure to infection, she ended up with typhoid pneumonia. She tried to ignore her symptoms until one of the doctors ordered bed rest. Her diary entry reveals her suffering and a sense of fear:

Sharp pain in the side, cough, fever and dizziness. A pleasant prospect for a lonely soul five hundred miles from home… Dream awfully, and awake unrefreshed, think of home and wonder if I am to die here as Mrs Ropes is likely to do.

Mrs Ropes was the matron of the hospital and had also contracted typhoid pneumonia. She was concerned about Louisa’s worsening state and had written to Bronson advising him to collect his daughter. On 20th January, Mrs Ropes died and Louisa agreed to return home. She had only served six weeks of her three month placement. The illness was lengthy. Following the journey home with her father it was eight weeks before she was able to sit up in bed. She had been feverish and suffering delusions for three weeks. Her hair was cut short, something which was common practice as an attempt to combat illness in the Nineteenth Century. She was finally able to leave her room in the spring, and wrote in her journal “I was never ill before this time, and never well afterward.” This refers to ongoing bouts of ill health which she began to experience a few years later. She had been given Calomel, a mercury compound, which was a popular remedy for many illnesses. For many years it was thought her health condition resulted from mercury poisoning, however, recent thinking disputes this and the theory now, is she may have developed Lupus.

Her letters home and journal entries were the inspiration behind what would become the novella Hospital Sketches. The material was first published as a series of letters in two instalments in The Boston Commonwealth, a known anti-slavery paper. The first instalment came out in May 1863, with the second instalment being eagerly awaited. The reading public were eager for knowledge of the war and little was known about life in the hospitals. In October it was published in book form under the title Hospital Sketches and Camp Fireside Stories and included eight additional short stories. The character starts out as “Topsy Turvy Trib” and is deliberately mocking of her own self importance and dedication. Alcott added a postscript to the novel defending:

the tone and levity in some portions of the sketches… It is a part of my religion to look well after the cheerfulness of life, and let the dismals shift for themselves.

The novel begins with Trib wanting to do something productive with her life but observing the only options open to her were matrimony, teaching, writing, acting or nursing. Of these, the least reputable would have been to become an actress. Employment was clearly an issue which concerned Alcott, and were explored again in a later novel entitled Work: A Story of Experience (1873).

Hospital Sketches begins prior to Trib’s journey to the hospital, which is re-named “Hurly-burly House”. Alcott’s frustrations at the bureaucracy she encountered form part of the early stages of Trib’s journey. Once in post, she is immediately put to work:

… with pneumonia on one side, diptheria on the other, five typhoids on the opposite, and a dozen dilapidated patriots, hopping, lying, and lounging about.

With each passing day, Trib becomes more deeply drawn into the effects of the war and moves from the persona of comic spinster to serious witness. The reader follows Trib’s movement from innocence to maturity. She becomes disillusioned by her experiences and shocked at the differences between the fabled and real war. The pithy tone of Alcott’s writing makes clear her outrage at examples of mis-management of the hospital, including the nailing shut of the windows. She describes the callous and indifferent attitudes of the surgeons, contrasted against the matron who would happily give up her food rations for the patients. She also criticises the hospital chaplain for the lack of comfort offered to dying men.

The novella is a curious text in that it blends the horrors of hospital life with a light hearted tone as we follow the exploits of protagonist Tribulation Periwinkle. When I taught this book a few years ago, my students observed the writing style felt quite modern. Indeed, the colloquial tone of the book serves to mediate some the unpleasant detail of the hospital ward. She was paid $200 for Hospital Sketches, and it was this publication which set her on the road to becoming taken seriously as Louisa Alcott, the writer.

Leave a comment